As The Mirage closes on Wednesday, a band of Las Vegas residents on social media worry for the future of one particular mallard on the property.

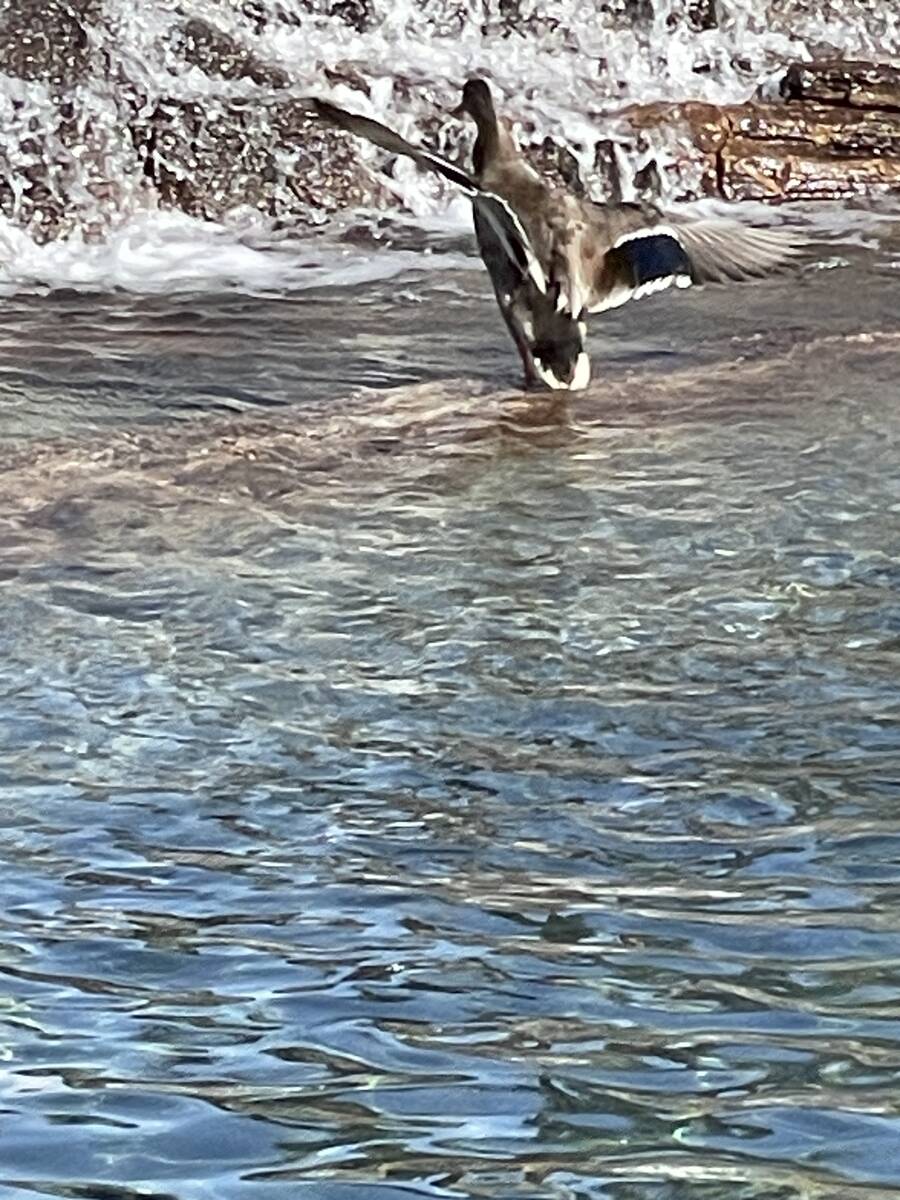

A mallard living in the pond around the famed Mirage volcano has seized the attention of Las Vegas residents, wildlife officials and a casino executive alike.

Despite a group of locals on social media banding behind the cause to save it before the casino closes Wednesday, the duck’s future remains uncertain.

A now-viral video says it will be re-homed at the Flamingo nearby, but Mirage officials said they have yet to relocate it. And it might be illegal to do so without consulting the Nevada Department of Wildlife, a department spokesperson said.

Las Vegas resident Krista Gifford said she began feeding the duck during the COVID-19 pandemic on her walks around the eerie, shut-down Strip. She lovingly named the duck George and soon noticed that it wasn’t able to fly out of the habitat like the other birds.

Her worry for the duck’s well-being grew as the Mirage closure date approached, Gifford said, causing her to reach out to casino and wildlife officials. A rare yellow-billed loon was removed from the Bellagio fountains earlier this year, but George’s common breed didn’t do him any favors.

“He can’t fly — I’m 100 percent certain,” Gifford told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “I don’t know what’s going to happen to him.”

Joe Lupo, president of The Mirage, said in a statement that relocating all of the property’s animals is a priority, whether the animal in question is a duck, big cat or dolphin. But Lupo doesn’t believe there’s cause for concern.

“There are no waterfowl in any danger as I communicated with those inquiring,” Lupo said. “We have always intended to take the appropriate care for relocation and have communicated with our friends at Caesars Entertainment and The Flamingo as a relocation site for the remaining waterfowl if necessary.”

Lupo has communicated with the Flamingo about having its animal sanctuary as an option for relocation, he said. The Flamingo’s parent company, Caesars Entertainment, didn’t respond to requests to confirm that.

Ultimately, though, state statutes call for the state wildlife department to lead any effort to move a wild animal. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 also could require involvement from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a federal agency.

Feeding any wild animal can cause issues

Doug Nielsen, spokesman for the wildlife department’s Southern Nevada office, told the Review-Journal that he hadn’t heard about George until the social media buzz.

A Mirage spokesperson said the casino has been in contact with the department since late last week, but Nielsen said the the urban wildlife program hadn’t heard from the casino about any specific injured animal as of Tuesday afternoon. The department did receive a call from the Mirage, however, asking for general information about whether birds would be harmed by the removal of the volcano, he said.

Wildlife officials walked the property twice — once on Friday and another time on Monday — and didn’t find any injured birds, he said. Gifford, the duck’s caretaker, said the only time George is visible is in the early morning hours when the animal has come to expect breakfast.

Generally, Nielsen said, the department prioritizes keeping wildlife wild when considering if or when to remove animals from a construction area. Most of the time, encouraging migratory birds to continue their journey is the right move.

“We take every situation on its merit,” he said.

Feeding wild animals makes them associate humans with food, Nielsen said. With wild birds, human food can even cause them to develop what’s known as “angel wing,” which can harm their ability to fly.

“There was an emotional connection to this duck, but has it been good for it in the long term?” Nielsen asked. “Probably not.”

Duck Destiny

What lies ahead for George isn’t definite.

Lupo, Mirage’s president, is allowing an animal rescuer to intervene and take him to a vet, a spokesperson confirmed. The plan is to take him to the Flamingo, but Gifford said the rescuer will decide if that’s the best course of action.

Nielsen said state wildlife officials weren’t involved in any of these plans.